Concert Dance in Israel

Israel is a society of Jewish immigrants who have returned to their ancient biblical homeland. It is also a complex society made up of people of varied cultures and ideologies, enduring changing economic and political situations. For the past eighty years, Israeli dancers have reflected and helped to shape the internal dialogues of Israeli life and contributed to a global exchange of dance ideas, especially with modern dancers from Europe and America.

The independence of ancient Israel came to an end in c. e. 73, when the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans after fierce battles with the Jews. The great revolt against Roman rule (132-135) failed, and in its wake the Romans banished the Jews from their country. Thus began a two-thousand-year exile, during which the Jews in the Diaspora preserved their religion, suffered anti-Semitic persecutions, and dreamed of returning to their land, to Eretz Israel – Zion.[i]

There are many biblical descriptions of dances in ancient Israel related to tilling the earth, mourning, military victories, joy, entertainment, and religious rites, suggesting a rich dance tradition. In the Diaspora, the dances related to the life of a people in its lands were lost. Gradually, Jews adopted the dances of the peoples with whom they lived. Family and religious rituals, especially marriage, became more and more important to Jews, especially as they were the only true joy left in the exiles people's lives (Friedhaber 1994, 1995). With the beginning of the Hassidic movement in the eighteenth century, dance became part of prayer. [ii]

The longing for Zion was expressed throughout the years in various modes, such as Messianism, immigration, and songs of longing. In the late nineteenth century, the Hibat Zion movement, a popular effort to populate Eretz Israel, came into being in eastern Europe. In 1882 its members established the first colonies in Eretz Israel which was followed by the World Zionist Federation (1897), chaired by Theodor (Binyamin Ze'ev) Herzl. The Federation's main aim was the revival of Israel and the foundation of an independent Jewish state there, to which all exiled Jews could return. One of the major decisions at this time was to revive the Hebrew language, a language that had been kept alive within religious contexts but not spoken vernacularly since Roman times.

The pioneers of artistic dance in Eretz Israel(Palestine)[iii] in the early twentieth century had to create dance "from scratch." At the time, although many Jews participated in concert dance, it had no Jewish voice.[iv] Various questions were asked in this context: What concert and folk dances should represent new Israeli society? What movement materials should new dances draw on? Should Israeli dance be created only when all immigrant cultures become fully assimilated in a "melting pot"?[v] Should creators turn to the classical ballet tradition or to modern dance? Should they turn to Europe, the United States, or the Middle East? Creators in all art fields were concerned about the direction Israeli art should take. Dance pioneers were on the verge of establishing the foundations of Israeli dance art and each felt zealously responsible for formulating an appropriate artistic concept.

The First Ones

For more than four hundred years, Palestine had been a province under Ottoman rule. Palestine contained neither professional dance, acting, or music schools, nor theater halls. The Ottoman's defeat in World War I resulted in the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. In 1918 Palestine was captured by the British and, effective from 1920, British administration was confirmed by a League of Nation's mandate. Jewish immigration to Palestine increased and its nature changed. In the past, immigrants had been mostly young, single idealists; now entire families were arriving, including many artists, most from Eastern Europe. They settled principally in the cities,[vi] boosting the development of the arts, including dance. These artists wished to create a nationalist Israeli art, maintaining the Jewish separatism and nationalism that had been typical of Eastern European Jews prior to their immigration to Eretz Israel.[vii]

Dance creators, like most other Israeli artists at the time, wished to express a link between the renewed Israel and the ancient one. They used archaeological relics and Hebrew scripture as inspiration, often making dances about biblical characters, thus expressing the continuity between the past and the present. To many artists, the Yemenite or Oriental (Mizrahi) Jews[viii] symbolized the authentic Israeli, the link between twentieth-century Jews and their forefathers, and many dances revolved around Mizrahi characters. Eastern European and Hora dances, artistically adapted to the stage, were also popular, their energetic, quick rhythms symbolizing the country's youthful revival. The Jewish Eastern European community was also a subject used to express the link to Jewish heritage, but most dancers regarded it as a symbol of the Diaspora from which they wished to be returned.

Unlike their ghettoized Eastern European and Russian counterparts, central European Jews, including many artists, were more urban and cosmopolitan. These immigrants strengthened the trend in Israeli dance that supported the dominance of European culture in Eretz Israel, claiming that Israeli dance should not be artificially created before it had time to develop naturally. They believed that the art to be created in Eretz Israel should reflect a modern view of the world. Quite naturally, Ausdruckstanz was the style that took root in a society based on socialist values. This dance style, standing for simplicity and freedom from tradition and opting for personal expression and social involvement, spoke to the heart of this generation of pioneers. Classical ballet, in opposition toAusdruckstanz, was generally rejected as an old-fashioned style, associated with either royal courts of past centuries or the bourgeoisie (Eshel 1991, 49-50).

The first Israelis to create artistic dance in the 1920s were the dancers and choreographers Baruch Agadati and Rina Nikova, and the teacher Margalit Ornstein. In 1920 Agadati presented a modern dance recital at the Eden cinema[ix] in Neve Zedek on the outskirts of Tel Aviv, to music by Béla Bartók and Arnold Schoenberg (Plate 1). Wishing to combine Middle Eastern and Western motifs, he turned to Hassidic and Yemenite dances. He also employed what he called Jewish gesticulation:

Gestures are characteristic of Jews. The Jew is generally full [of] movement, never talking without his hands, and when he dances, he wishes to explain. My aim in dance is to express this particular movement (Agadati 1927, n. p.).

Agadati was also a painter, and he designed costumes for his dances styled after cubist and constructivist painting. From 1924 to 1929 he toured Europe with his dances (Manor 1986, 7-14).

Two years after Agadati's recital, Margalit Ornstein, who had immigrated to Eretz Israel from Vienna, established the first dance studio in Tel Aviv. As was common practice for upper-middle-class girls in Vienna at the time, Ornstein had studied Mensendieck gymnastics and Dalcroze eurhythmics. Her students practiced in white tunics, their hair tied in a bow, as was common in Europe following Isadora Duncan. When her daughters, Yehudit and Shoshana, were sixteen, they opened branches of the Ornstein Studio in Haifa and Jerusalem. During family visits to Europe they studied with teachers such as Rudolf von Laban, Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, Elinor Tordis, and Gertrud Bodenwieser. Margalit Ornstein also choreographed the movement for the first plays presented by the Eretz Israeli Theater, founded in 1925.

Plate 2: Rina Nikova and her Corps de Ballet in Russalka.

Rina Nikova immigrated in 1924 from St. Petersburg where she had studied character dance and classical ballet. In Tel Aviv, she became a ballerina in the Eretz Israeli Opera, founded that year by the conductor Mordechai Golinkin[x] (Plate 2). She danced on a floor covered with oriental rugs, usually accompanied by one man and three women who constituted the corps de ballet. When the Opera was closed in 1929, she traveled to the United States where she became acquainted with the work of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn in Denishawn Company where they produced dramatic dance scenes of Oriental life. Upon Nikova return to Tel Aviv in 1933, she founded the Yemenite Company, where young Yemenite girls (of whom the most notable was Rachel Nadav) performed dances on biblical themes. The dance material was based on folkloric dances and songs of the Yemenite Jews, adapted for the stage. The company, with beautiful costumes and impressive staging, successfully toured Europe between 1936 and 1939. The impresario Sol Hurok planned an American tour for them, but as World War II began the tour was canceled; the company returned to Tel Aviv and disbanded.

Sudden Growth

Immigration from central Europe increased in the early 1930s and the population of Tel Aviv reached eighty thousand. Many international artists, including dancers, appeared there, for example, Gertrud Kraus, the dancer and choreographer from Vienna, Pauline Koner from the United States, Ruth Sorel from Poland, the child prodigy Mussia Daiches,[xi] and the Indian dancer Uday Shankar.

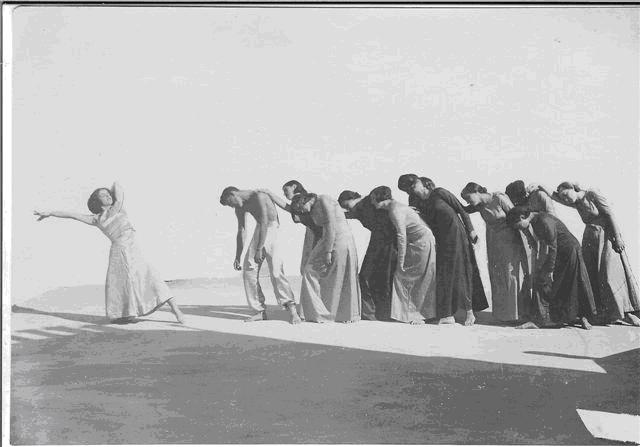

In the early 1930s, a second generation of Israeli dancers emerged. Most of them had immigrated at a young age, including the twins Yehudit and Shoshana Ornstein (Plate 3); Deborah Bertonoff from Russia, a dancer-actress who specialized in character portrayal; and Dania Levin from Turkistan, who founded the Movement and Speech Company in Tel Aviv (1931). Dancer Yardena Cohen was a sixth-generation Israeli. Since there were no dance schools apart from the Ornstein Studio (which did not have advanced studies) dancers traveled to Europe in order to study with Ausdruckstanz teachers, especially Mary Wigman, Kurt Jooss, Gret Palucca, and Vera Skoronel.

Plate 3: Yehudit Orenstein and Dance Group, 1945.

Among the immigrants arriving in Eretz Israel following the Nazis' rise to power in 1933 were also the first professional Ausdruckstanz dancers and teachers, including Tille Rössler, who had been a principal teacher at Gret Palucca's school in Dresden, and the dancers Else Dublon, Paula Padani, and Katia Michaeli, who had danced in Mary Wigman's company. In 1935, at the peak of her artistic success as a notable dancer and creator in theAusdruckstanz style in Central Europe, Gertrud Kraus decided to immigrate to Eretz Israel. As a dancer, she was famous for her temperament, but she also created a string of unaccompanied minimalist Israeli landscape dances, such as Night and Sun (Manor 1979, 67-73). She commented on her encounter with the "Orient":

There is European Orientalism. It is sweet and sentimental. The dancer spreads her hands like two snakes. But our Orient is not sweet. It is wild and stormy, as well as naïve and crude. … In Europe I guessed the Orient, but when I came here – I waited. I waited until I developed in myself the sense and the confidence of one who had taken root. (Ben-Ami 1948, n. p.)

The sudden increase in the number of dance artists resulted in the National Dance Competition among Israeli dancers, which took place in Tel Aviv in 1937 (Spiegel 2000); the winner was Yardena Cohen, who presented dances on biblical themes and Mizrahiwomen. Although she had studied with Palucca in Dresden, Cohen based her dance on movement materials from the folkloric dances of the Arabs and bedouins with whom she had grown up as a child. The dances were accompanied by Mizrahi Jewish musicians playing the oudh and oriental drums, and singing Arab, Turkish and Hebrew tunes (Cohen 1963, 27). It is interesting to note the reserved criticism of the critic Lea Goldberg:

Yardena Cohen dances Mizrahi dance. We Jews, who have wandered around Europe for 2,000 years, who have listened to Beethoven and seen the Russian Ballet, the modern dance companies from Isadora Duncan onwards – is this our sense of the Orient? Are we capable of reacting to its hot dry weather like a Bedouin woman reacts to it? (1937, n. p.).

And the critic Haim Gamzu wrote:

[Yardena Cohen's] identification with the Arab rhythm is mental, not merely mimicry. Here we find the perfumes of the Orient, and something more that can be heard by those Europeans who know how to listen. In this dance there is measured, balanced discipline, finding expression in restricted movement. There is no release of the body, of its burden of senses and desires and longings (1937, n. p.).

These are examples of an abundance of articles published at the time, expressing the pros and cons of assimilation with the Orient and arguing over how it should be accomplished.

The Isolation Years

When World War II broke out, cultural ties with Europe were severed and Israeli dance artists became isolated for more than ten years.[xii] Culturally, the Jewish settlement in Eretz Israel in the 1940s was an island of prosperity in a war-ridden world, and ambitious to become a cultural center. The separation from Europe increased the reliance upon local talent, and there were many dance recitals and performances by teachers and their students; artists were driven to create, and there was public demand for their works.

In the wake of rumors from Europe about the extermination of millions of Jews by the Nazis in concentration camps, artists turned to escapism and embraced romantic themes:

Nowadays, there is a tendency to return to traditional forms. To avoid dissonance, to achieve harmony as much as possible. … Nowadays, the fear of the future is great, and there is too much weariness of the present (Goldberg 1943, n. p.).

Dancers gave many recitals in difficult conditions, with no sets, accompanied by a pianist. Special costumes were made for each dance (often a performance included ten short dances), long, flowing gowns of fine cloth, forming one line from head to feet, accentuating the torso's expressive movement. The costume designers were usually painters of the Paris school.

Dancers adopted the ideas of Rudolf von Laban, who had studied the laws of movement and had taught that a conceptual message can be expressed through composition and the use of dynamics, time, and space. But their practice did not correspond to his theory, and they expressed their ideas in a theatrical, overly-mimetic style (Roth 1944, 49-51).

The main Israeli dance figure of the time was Gertrud Kraus, who not only gave solo performances and established a teaching studio in Tel Aviv, but also founded a modern dance company connected to the Folk Opera (1941-1947) (Plate 4). In addition to dances integrated into the operas, the company also presented all-dance programs (since there were no male dancers, those roles were danced by women) (Manor 1978, 73-75). The company was comprised of Kraus's students, including Naomi Aleskovsky, Rachel Talitman, Vera Goldman, and Hilde Kesten. Kraus encouraged her students to create, and they presented their own recitals and became artists in their own right. The dance community was later joined by other dancers, including Hassia Levy-Agron,[xiii] who was to found the dance department at the Jerusalem Academy of Music and Dance.

Plate 4: La Belle Hélène (1936) choreographed by Gertrud Kraus, as performed by her group at the Folk Opera.

In 1947 the Folk Opera disbanded and with it Kraus's company. A year later, when the State of Israel was founded, Kraus left for the United States. She declared, "I am going there to show a new artistic style [created in Eretz Israel], and I am certain that I will also see a new style there, a style searching for its path in the routes of Modernism" (quoted in Ben-Ami 1948, n. p.). In the United States she met Martha Graham, Agnes de Mille, Antony Tudor, and others. Naomi Aleskovsky, a dancer in Kraus's company, recalls:

She saw developed modern dance and dancers doing things she had never dreamed were possible. She returned to Israel as if struck by lightning. She had lost her confidence. The fact that she had no framework to return to at the time made it more difficult for her to find herself again (1991).

Kraus's personal crisis heralded the crisis of Israeli Ausdruckstanz artists in the 1950s.

As aforementioned, unlike the Ausdruckstanz style that was welcomed by the pioneer society, classical ballet was rejected as bourgeois art. And yet, in 1936 Valentina Archipova-Grossman, an immigrant from Latvia, established a dance studio in Haifa, teaching future generations of teachers. Mia Arbatova, formerly a dancer at the Riga Opera, opened a ballet studio in Tel Aviv in 1938, teaching generations of dancers and creators. However, throughout the development of dance in Israel, classical ballet was marginal to modern dance (Eshel 2000a, 2-8).

During those years, the first Israeli folk dances were created, seeking to replace the folk dances that the pioneers had brought from their countries of origin. The active spirit in this enterprise was Gert Kaufman (she later used the name Gurit Kadman), who believed that dancers should create Israeli folk dances instead of waiting for them to evolve (Friedhaber 1989). Already in 1943, she published the first instruction booklet, Folk Dances – Twenty Two Dances. Another important creator of folk dances was Rivka Shturman, a member of Kibbutz Ein Harod (Sharett 1988). [xiv]

The folk dances that were created in Eretz Israel in the 1940s drew from four sources: folk dances, mainly from eastern Europe, Hassidic dance, Yemenite dance, and Arab debka dance. In 1944 the first Folk Dance Assembly took place in Kibbutz Daliah (Ashkenazi 1992). Some of the dances were taken from pageantsthat were created principally in kibbutzim, aimed at reviving the nature holidays of ancient Israel and creating new popular feasts. The performance, presented outdoors, was a total event: it combined a reciting chorus, a singing choir, and a mass dancing performance (Goren 1983; Cohen 1963). Most of the professional Ausdruckstanz dancers created such pageants, which matched the vision of Laban, who considered the creation of new popular dances by amateurs one of the goals of modern dance (Eshel 2000b, 72-76). Among the notable creators were Lea Bergstein, who prior to her immigration to Eretz Israel from Vienna had danced in Vera Skoronel's company, and Yardena Cohen. Quite a few of the artistic dances for amateurs that were created for those pageants later became folk dances. In some of the kibbutzim, such performances are a tradition carried out to this day.

When the State of Israel was founded in 1948, many artistic endeavors were supported by the state, but artistic dance was not; it was still viewed as elitist, while folk dances were considered acceptably socialist.

The 1950s Crisis – A Transition

The early 1950s were years of economic crisis in Israel: recovering from the War of Independence while absorbing thousands of immigrants, placed in tent camps around the country. Food was rationed and people could not afford to travel abroad. After a long period of isolation, guest companies from Europe and the United States began appearing.[xv]

Martha Graham's first company tour of Israel in 1956, a visit arrangedby Baroness Bethsabee de Rothschild, left a strong impression.[xvi] People realized that Ausdruckstanz had faded from the global dance stage, and that American modern dance was now an important form. The visiting dancers' sharp, polished technique and the innovative sets and lighting astonished the audience in Israel and set new standards for dance performances. Israeli dancers and choreographers lost confidence as audience appreciation grew for whatever came from abroad.

In 1952 Kraus founded the Israeli Ballet Theater, which was to present only two programs. She asked Talley Beatty, whose company had performed in Israel, to create for the new company, but the encounter between him and the dancers-accustomed to theAusdruckstanz style and to a joint improvisational process with Kraus-was difficult. One of these dancers, Arieh Kaleb, recalls, "Beatty tore us apart. We had to crawl on our knees until they bled. He wouldn't give up. He didn't care. The movement material was forced. He [Beatty] was lonely, and the company was lonely. No connection was made" (1988). Beatty's Fire in the Mountains got good reviews, while Kraus's own choreographies were called pathetic, criticized for lack of technical skill and "lack of expression in torso and limbs" (Shitu 1951). The Israeli Ballet Theater was the last, unsuccessful attempt to establish Ausdruckstanz on the professional stage without financial support.

Graham and Beatty were not the only American influences on Israeli dance. Ruth Harris introduced jazz dance in Israel. She was originally from Berlin but immigrated to the United States before moving to Israel. Fred Berk and Katia Delakova, who had danced in Kraus's company in Vienna before immigrating to the United States, toured Israel in 1949. Delakova returned to Israel alone for a period of years. Berk remained in the US and became one of the pillars of Israeli folk dance in the United States through the 92nd Street Y and the festivals he developed.[xvii]

The younger generation of American dancers, including Rina Shaham and Rena Gluck, were Graham trained, and each one of them opened a studio for modern American dance in Tel Aviv. Gluck focused on Graham's method and became its most important teacher at the time. Israeli dancers left the studios of teachers in the Ausdruckstanz style and flocked to the studios of these young dancers newly arrived from the United States.

The American dancers were not too familiar with the Ausdruckstanz style of German dance; like other Americans, they probably identified it with Nazi Germany. This style had been rejected in America and the young American dancers were unfamiliar with its history, its proponents, and its technique. Neither were they familiar with the work of their predecessors in Israel, since it had not been exposed abroad. In Gluck's words, "I felt like I was bringing a new light with me, like I was breaking new ground, doing pioneer work" (1989).

Like former generations of artists, those arriving from the United States received no state support, and thus presented recitals, taught, and established semiprofessional companies destined to be disbanded after a few performances. They were joined by young Israeli dancers who had returned to Israel from the United States after studying with Martha Graham or at Juilliard. In 1962 Anna Sokolow founded the Lyric Theater, which lasted for two years. The repertory consisted mainly of important works she had created for other companies, including Lyric Suite, Dreams, and Rooms. Sokolow came on visits but did not settle in Israel, and the company's work was constantly interrupted, since she did not allow them to perform in her absence or to present works by other choreographers.

Unlike the crisis in artistic dance that occurred whenAusdruckstanz was pushed aside and modern American dance was taking its first steps, the folk dance project continued to flourish. In 1949 Gurit Kadman published the first of the Let's Dance booklets, which grew in the following eight years to present fifty dances and basic dance terms in Hebrew, coined in collaboration with the Hebrew Language Academy. The most notable creator was Yonatan Karmon, who presented artistic performances in popular style. In 1958 he established the Karmon Company, which was to appear on stages worldwide for twenty-five years. Many Israeli folk dance companies imitated his style. Israeli folk dances also found their way into Jewish communities abroad, mainly the United States.

Unique Developments

Just when Israeli dance was being dwarfed by foreign dance, two important projects were developing in Israel: the Noa Eshkol-Abraham Wachman Movement Notation system, and the Inbal Dance Theater. Noa Eshkol and Abraham Wachman invented a notation method based on geometry and mathematics that enabled an objective description of potential movements and their combinations (useful in dance, research, and teaching). In 1954 Eshkol founded a Movement Quartet that danced works created in Movement Notation. She published dozens of books from the 1960s onward, often written in collaboration with Israeli Movement Notation researchers whom she trained.

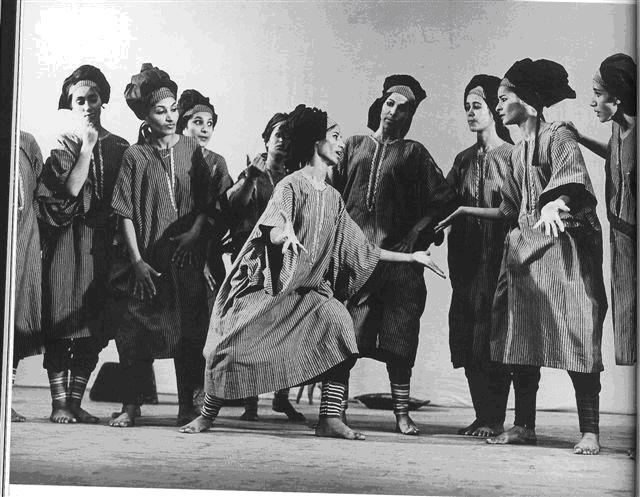

When Jerome Robbins visited Israel in 1951, the American Fund for Israeli Institutes asked him to suggest an Israeli dance company that should tour abroad. He recommended the Inbal Dance Theater, founded two years previously by Sara Levi-Tanai (Plate 5). Thus, Inbal Dance Theater became the first supported Israeli company, and was invited to tour in the United States in 1957. Robbins asked Sokolow to prepare the company for the tour, and that began her connection to Israel (by 1962 she founded the Lyric Theater).

Sara Levi-Tanai's approach to choreography was based on her interest in literature and philosophical ideas, often as expressed in the Bible and other ancient Jewish writing, and in the ideals of the Zionist pioneers. (Plate 5) The basic Yemenite movement, the da'asa step-a pliant, undulating, up-and-down movement performed by male Yemenite dancers-served as her inspiration. She often said that this dance step relayed the image of bare feetwalking on the soft dunes of the desert (Manor 2001).Inbal's most notable dancer was Margalit Oved. Although Inbal Dance Theater was accepted abroad as a representative of Israeli artistic dance, in Israel it was considered an ethnic folklore company and it remained outside the central circle of artistic dance endeavor.

Plate 5: Women, 1957, choreographed by Sara levi-Tanai for Inbal Dance Theatre.

Following his visit to Israel, Robbins presented the American Fund for Israeli Institutes with a report on dance in Israel. He found that, "in Israel, that there was much too much desire to feel the link [to ancient Israel], and to feel an Israeli culture, and absolutely no technique as to how to go about feeling it" (July 1952). In an attempt to allay the fear that studying "foreign techniques" may stunt the creation of Israeli dance, he wrote:

There is no such thing as a foreign technique to a dancer. There are no dances (to a true dancer) which are alien. Everything you are being taught, and particularly the modern and ballet technique, whether they come from Europe or Zululand, is a result of years and years of experimentation and development. You must learn these techniques to have mastered them, and only after can you be in the position to continue experimentation, growth and development, making these various techniques into your own, so they are no longer alien, no longer strange, no longer foreign (Ibid).

The Big Companies – Turning to American Dance

In 1964 Bethsabee de Rothschild founded the Batsheva Dance Company. This was a turning point in Israeli dance; the period of Ausdruckstanz was over and that of American dance had begun.

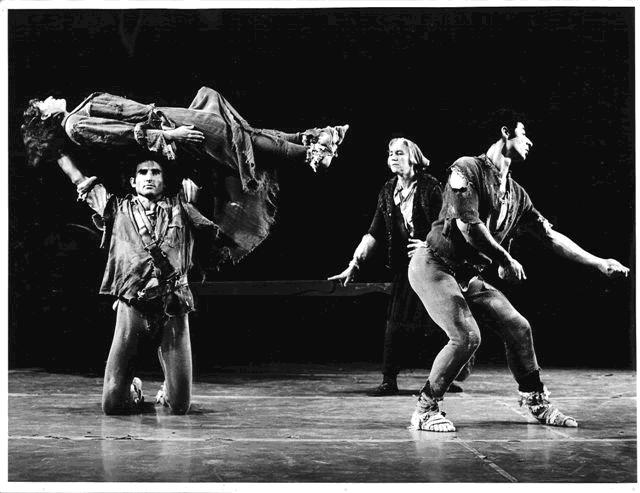

Rothschild wished to create a professional arena for Israeli dancers. Martha Graham, whose programs Rothschild had produced for years, became Batsheva Company's artistic adviser. Graham let the company perform seven of her works[xviii] alongside works by leading choreographers such as Robert Cohan, Donald McKayle, Glen Tetley, Norman Morrice, Talley Beatty, José Limón, and Norman Walker and by Israeli company members Oshra Elkayam, Rina Schenfeld, Moshe Efrati, and Rena Gluck (Plate 6).

Plate 6: The Brood (Mother Courage), 1968,choreographed by Richard Kuch and performed by members of Batsheva Dance Company.

In 1968 the Israeli Ballet was founded by the dancers Bertha Yampolsky and Hillel Markman. Until the 1980s, the Ballet's repertory included works mainly by guest choreographers from abroad such as Félix Blaska, Gene Hill-Sagan,[xix] Janine Charrat, Joseph Lazzini, and Heinz Spoerli. The repertory also included works by George Balanchine.[xx] For the past twenty years, most of the Israel Ballet's repertory of dramatic, abstract and contemporary dances have been created by Yampolsky in a highly aesthetic, technically demanding, neoclassical style.

Following a disagreement between the Batsheva Company and Rothschild over the status of ballet dancer Jeannette Ordman in the company, Rothschild founded a second troupe, Bat-Dor Company, in 1967. Ordman became its artistic director. Although both companies had a modern repertory, unlikeBatsheva's focus on the Graham technique, Bat-Dor emphasized modern dances that incorporated ballet technique. Among the first choreographers to work with the company were Antony Tudor, Rudi van Dantzig, Lar Lubovitch, Alvin Ailey, Manuel Alum, and Paul Taylor and the Israeli Domi Reiter-Soffer. A dance studio was founded alongside the company, training most of the next generation of dancers in Israel.

In the mid-1970s and early 1990s a large number of immigrants from the former Soviet Union came to Israel, among them ballet dancers, some of whom joined the Israeli Ballet. Thanks to these immigrants, the size of ballet audiences has significantly increased in Israel.

In 1969 the Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company was founded, and in 1973 Yehudit Arnon became its artistic director. The company moved to its permanent base in Kibbutz Ga'aton near the Lebanese border–the first company in Israel not to be based in Tel Aviv-responding to the needs of members who wished to dance while still living on the kibbutz (Eshel 1996, 129-135). For the first ten years, the company's dancers were required to keep their regular jobs on their home kibbutz while dancing with the company. They could only gather for rehearsals and performances for a few days each week, and the company's technical level was low. The company enjoyed increased recognition beginning in the 1980s, when Jirí Kylián formed a special connection with the company and it performed some of his works, including La Cathédrale Engloutie and Stoolgame, and in the late 1980s, when it performed Mats Ek's works Fire Place and Down North. Nowadays, all the dancers live on Kibbutz Ga'aton and their daily schedule resembles that of any professional company. Rami Be'er, a former company dancer who began choreographing for the group in the late 1980s, became artistic manager in 1997. Its present repertory is based mainly on his works, influenced by German and American dance. Be'er's dances address issues of the Kibbutz Movement, the individual's loneliness in the city, problems of second-generation Holocaust survivors, and the Palestinian Intifada (Rottenberg 2000, 12).

In 1978 the dancer and choreographer Moshe Efrati left Batsheva Company and founded the Kol Demama (in Hebrew, sound-silence) Company. For a decade, it was comprised of both hearing and hearing-impaired dancers. Efrati invented a method of passing vibrations through floorboards as a substitute for sound, allowing the hearing-impaired dancers to sense the vibrations through their feet. Since the 1990s, there have been only hearing dancers in the company. Efrati, a Jerusalemite with Mizrahi roots, is concerned with Jewish tradition. The theme of his work Psalms of Jerusalem (1982) was the three main religions sanctifying the city, and Camina y Torna (1992) was created to mark the quincentenary of the Jews' expulsion from Spain.[xxi] He has also addressed topical issues of Israeli society: La Folia (1989) dealt with social tensions, and in Myth (1995) he opposed the shattering of the pioneer myth in Israel. The company disbanded in 2000.

Between 1964 and 1976, all professional dance activities in Israel took place in professional companies. This improved Israeli dancers' technical and teaching standards and their tours placed Israeli dance on the global map.

Batsheva and Bat-Dor, the leading companies, competed over important choreographers from around the world, and did not easily open their gates to Israeli choreographers (Eshel 1994, 84-92); local creativity diminished.

Support for Batsheva's Israeli choreographers decreased after the firstfew years, as Rothschild lost interest in the company. Other than company dancers, Mirali Sharon was the only Israeli choreographer who created for Batsheva. Sharon returned to Israel after studying with Merce Cunningham and Alwin Nikolais and establishing her own small, well-reviewed company in New York. Sharon also created some works for Bat-Dor.

The Breakthrough of Fringe Dance

In the mid-1970s, modern dance in Israel began to show signs of weariness. The dramatic, thematic approach as well as the movement idiom and artistic concept became repetitive. At that time, several young female choreographers who had studied abroad returned to Israel. They were familiar with new American postmodern dance, having seen experimental works in Judson Church in Greenwich Village in New York. For Israeli choreographers, this dance legitimized a revolt against the canons of modern American dance as performed by the major dance companies in Israel. The returning choreographers made local dancers and creators aware of the possibility of life outside the big companies. Among them were Rachel Cafri, who studied with Merce Cunningham; Hedda Oren, who studied with Alwin Nikolais; Ronit Land, who returned from Britain after attending a course for young choreographers in the New Dance style; and Ruth Ziv-Ayal, who studied at New York University.

In 1976 the Merce Cunningham Company performed in Israel and had an enthusiastic reception, although his style never caught on. Many articles were published in the newspapers on his and Yvonne Rainer's artistic perceptions. In the spirit of Cunningham's collaboration with John Cage and Robert Rauschenberg, tight ties began forming in Israel among fringe choreographers, visual artists, and composers of electronic music. Creators embraced new notions of dance based on everyday gestures, distanced from virtuosity or canonic style. However, Israeli choreographers refused to reject theatricality, narrative, message, and emotion. These creators favored Carolyn Carlson, Meredith Monk, and Kei Takei who performed in Israel and gave workshops.[xxii]

In 1976 Ruth Ziv-Ayal created Secret Places, the first Israeli work in movement-theater style. The performance was a modern legend of sorts: a young couple comes up against imaginary figures who personify daily objects such as silverware, buttons, bowls, ropes, and keys. In 1977, my own first dance recital took place with dances created by Ronit Land, Hedda Oren, Ruth Ziv-Ayal, and Rachel Cafri. Later, I founded chamber groups and created dances for them as well as for my own recitals (until 1986), revolving around natural materials and rituals. Dorit Shimron founded the Tnuatron in 1977, companies of young girls combining dance and acrobatics with objects. A year later, Rina Schenfeld, the leading Batsheva dancer, performed her first solo recital, Threads, based, like her following works, on the use of objects. Flora Cushman, a former teacher in Maurice Béjart's Mudra, founded the Jerusalem Dance Workshop in 1978. Some of these works may be described as movement-theater or postmodern dance.

In 1975 the Dance Library of Israel was founded in Tel Aviv (as part of the Music Library), initiated by Anne Wilson Wangh and Estelle Sommers from the United States. It was greatly expanded when it became an independent body in 1984, directed by Gila Toledano and with Giora Manor serving as artistic adviser. Since 1997, it has been directed by Talia Perlstein. The library includes books and videotapes of international dance as well as archives documenting the development of dance in Israel.

Back to Europe

In 1981 Pina Bausch came to Israel with the Wuppertal Dance Theater for the first time, and the local dance community became familiar with the Tanztheater style. For about five years before that visit, experimental dance works had been created in Israel, some of them in the movement-theater style, and Bausch's visit reinforced that tendency, providing local creators with more tools. As her roots are in Ausdruckstanz, Bausch's performances awakened the historic connection that Israeli dance has with German dance (Eshel 2001). American postmodern dance began to seem too conceptual to Israeli creators. The creative upsurge following Bausch's visit to Israel was immediate. The following year, Nava Zuckerman founded Tmu-Na Theater, and Oshra Elkayam-Ronen-previously identified as a choreographer for Batsheva, considered "established dance" in Israel-founded the Oshra Elkayam Movement Theater. Like Bausch, they were concerned with gender issues, social norms, and the lack of communication between people. In the 1980s fringe dance in Israel was enriched by more dancers and creators, including Mirali Sharon,[xxiii] Sally-Anne Friedland, Tami Ben-Ami, Yaron Margolin, Tamara Mielnick, Alice Dor-Cohen, Nir Ben-Gal, and Liat Dror. Meira Eliash-Chain and Zvi Gotheiner with founded with former dancers of the Batsheva Company the Ramle Company [Tamar] (1983), later the Tamar-Jerusalem Company headed by Amir Kolben, which focused on Israeli-Palestinian political issues. Increasing fringe activity brought about the establishment of Shades in Dance project (1984), in which works by young fringe artists were exposed on a professional stage, and in 1990 the first of the Curtain Up events, premieres of works by known fringe creators, took place. In 1989 the Suzanne Dellal Center was founded, managed by Yair Vardi, and became the central home of Israeli dance.

In the past decade, a large group of young, experienced Israeli creators and dancers have worked in established big companies and in marginal, fringe frameworks. Among the most notable creators and companies are Ohad Naharin (Batsheva Dance Company), Rami Be'er (Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company), Nir Ben-Gal and Liat Dror (The Group), Noa Wertheim and Adi Sha-al (Vertigo Dance Company), Anat Danieli Dance Company, Amir Kolben (Kombina Company), Ido Tadmor Dance Company, Tamar Borer, Yossi Yungman, Emanuel Gat, Sharon Eyal, Noa Dar Dance Company-Holon, Muza Dance Company, Inbal Pinto Dance Company, Barak Marshal Dance, and Yasmeen Godder. Inbal Dance Theater and the Israeli Ballet are still active. In 1998 Valery Panov[xxiv] established the Ashdod Ballet, in which all the dancers are immigrants from the former Soviet Union.

The 1950s belief that Israeli art would be created out of a melting pot has changed. The Cultural Document-Vision of 2000, presented to the Minister of Science, Culture and Sports, formulates the following ideas: "In Israeli culture of the 21st century there is room for all groups that wish to culturally express their emotions, values and history. … However, recognition of legitimacy and plurality does not legitimize a split cultural reality without any common denominator." There are many ethnic companies in Israel: Russian, [xxv] Arab, Bukharan, Caucasian, Druse, Yemenite, and Ethiopian.[xxvi] Flamenco and oriental dance are performed, including in an original encounter between the flamenco dancer Neta Sheazaf and belly dancer Elina Pechersky. Another manifestation of the relation between folklore and artistic dance is the Beta Dance Troupe which creates contemporary dance inspired by folklore.

The yearly Karmiel Dance Festival in the Galilee established in 1988 and directed by Yonatan Karmon, draws thousands of people who come to dance folk dances for three days and nights. The festival program includes hall performances as well as mass dances in public parks and in the streets; folk dance, ethnic dance, and artistic dance are all combined.

After forty years during which Ausdruckstanz was created in pioneer conditions, when creativity was not supported by technical skill; after fifteen years of modern American dance, raising technical levels but privileging choreographers from abroad; after fifteen years of fringe development, bringing about an abundance of local creators-finally, in the 1990s, Israeli dance has reached maturity. A balance has been reached between dance in large companies and in the rich fringe, and between creativity and technique. Most importantly, Israeli creators are sensitive to the particular time and place in which they live, giving form to Israel's varied cultural identities, unique history, and contemporary problems.

Works Cited

Agadati, Baruch. 1927. "Israeli Dance." Hatsfira 236, October 17. [Hebrew]

Ashkenazi, Ruth. 1992. The Story of the Folk Dances at Kibbutz Daliah. Haifa: Tamar.

Ben-Ami, Nachman. 1948. "On a Mission for Israeli Dance." Al Hamishmar. [Hebrew]

Cohen, Yardena.1963. The Drum and Dance. Tel Aviv: Sifriat Poalim. [Hebrew]

Eshel, Ruth. 1991. Dancing with the Dream: The Development of Artistic Dance in Israel 1920-1964. Tel Aviv: Sifriat Poalim and the Dance Library of Israel. [Hebrew; English Abstract]

—–. 1994. "Batsheva and its Israeli Choreographers." Israel Dance 4 (October): 84-92. [Hebrew]

—–. 1996. "Before the Beginning: The Prehistory of the Kibbutz Dance Company." Israel Dance 9 (November): 129-135. [Hebrew]

—–. 2000a. "Classical Ballet: Israeli Dance's Stepson." Dancetoday 2 (July): 82-93. [Hebrew and English]

—–. 2000b. "Hips Swirl like a Mobile in Kibbutz Ein Hashofet-Celebrating pageants in the valley and in the mountains." Dancetoday 1(April): 72-76. [Hebrew and English]

—–. 2001. "Movement Theater in Israel 1976-1991." Ph.D dissertation. Tel Aviv University. [Hebrew; English Abstract]

Friedhaber, Zvi. 1989. Gurit Kadman: Mother and Bride. The Jewish Archive. [Hebrew]

—–. 1994. "Jewish Dance Traditions Through the Ages, Part I." Israel Dance 3 (March): 57-58; "Jewish Dance Traditions Through the Ages, Part II." Israel Dance 4 (October): 116-117. [Hebrew and English]

—–. 1995. "Jewish Dance Traditions Through the Ages, Part III." Israel Dance 5 (April): 88-89. [Hebrew and English]

Gamzu, Haim. 1937. "Artistic Notes." Ha'aretz. [Hebrew]

Goldberg, Lea. 1937. "Criticism Column." Davar, October 29. [Hebrew]

—–. 1943. "Gertrud Kraus Ballet at the Popular Opera." Davar. [Hebrew]

Goren, Yoram. 1983. Fields Dressed in Dance. Kibbutz Ramat-Yohanan. [Hebrew]

Ingber, Judith Brin. 1985. Victory Dances: The Life of Fred Berk. Tel Aviv: The Dance Library of Israel. [Hebrew]

Levi-Tanai, Sara. 1999. "A Personal Testimony." In Barefoot: Jewish-Yemenite Tradition in Israeli Dance. Edited by Naomi Bahar-Ratzon. Tel-Aviv: Ele Betamamar. [Hebrew]; English translation by Robert Rees in Jewish Folklore and Ethnology Review 20 (2000): 93-122.

Manor, Giora. 1978. The Life and Dance of Gertrud Kraus. Tel Aviv: Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House. [Hebrew and English]

—–. 1986. Agadati – The Pioneer of Modern Dance in Israel. Tel Aviv: Sifriat Poalim and the Dance Library of Israel. [Hebrew and English]

—–. ed. 1991. The Choreography of Sara Levi-Tanai. Inbal Dance Theatre – The Ethnic Multicultural Center Inbal. [Hebrew and English]

Perstein-Kaduri, Tali. 2002. "Hassia Levy-Agron: Expressing the Sun and the Stars in Movement," Dancetoday 7 (January): 60-64. [Hebrew and English]

Robbins, Jerome. 1952. Letter to Judith Gottlieb, The American Fund for Israeli Institutes, July. In the archives of the Dance Library of Israel.

Ronen, Dan. 2000. "Dance for Everyone: On Multi-Culturalism in Israel and its Influence on the Development of Dance." Dancetoday 3 (November): 84-s89. [Hebrew and English]

Roth, Shlomit. 1944. "The Art of Dance and the Dancer." Bama 41 (February): 49-51. [Hebrew]

Rottenberg, Henia. 2000. "Between Abstraction and Expression – The Choreography of Rami Be'er." Dancetoday 1 (April): 12-18. [Hebrew]

Sharett, Rina. 1988. "Kumah E'ha"-The Story of Rivka Shturman, Pioneer of Israeli Folkdance. Hakibbutz Hameuchad Publishing House. [Hebrew]

Shitu. 1951. "Some Notes on the Second Performance of the Israeli Ballet Theater." Ayin (October): 10. [Hebrew]

Spiegel, Nina. 2000. "Cultural Formulation in Eretz Israel: The National Dance Competition of 1937." Jewish Folklore and Ethnology Review 20: 24-38. [English]

Interviews by the author

Aleskovsky, Naomi. 1991. Tel Aviv, February.

Gluck, Rena. 1989. Ramat-Aviv, December.

Kaleb, Arieh. 1988. Herzelia, April.

Plates

Plate 1. Dancer and choreographer Baruch Agadati in Yemenite Ecstasy, 1920. Courtesy of the Dance Library of Israel.

Plate 2. Rina Nikova and her Corps de Ballet in Russalka. Presented at the Eretz-Israeli Opera in 1926.

Plate 3. Yehudit Ornstein and Dance Group, 1945.

Plate 4. La Belle Hélène (1936) choreographed by Gertrud Kraus, as performed by her group at the Folk Opera. Courtesy of the Dance Library of Israel.

Plate 5. Women, 1957, choreographed by Sara levi-Tanai and performed by Margalit Oved and members of Inbal Dance Theatre. Photograph by Mula-Haramaty. Courtesy of Inbal Dance Theatre.

Plate 6. The Brood (Mother Courage), 1968, choreographed by Richard Kuch and performed by members of Batsheva Dance Company: Moshe Romano, Nurith Stern, Jane Dudley, and Yacov Sharir, and. Photograph by Mula-Haramaty. Courtesy of the Dance Library of Israel.

Notes

This article was originally published in Dance Research Journal, 35/1 Summer 2003, pp. 61-81

- [i]. Zion is the biblical appellation of Jerusalem and the Land of Israel; Eretz Israel literally means the Land of Israel. See note 3 for a discussion of the term Palestine and further discussion of Eretz Israel.

- [ii]. The Hassidic sect of Orthodox Judaism developed as a mystical movement in Eastern Europe in the eighteenth century. Hassidic Jews traveled to Eretz Israel and there were Hassidic communities there, too, who believed that dance is an integral part of prayer, since the ecstasy of dance brings them closer to God.

- Palestine was the region's political name in this period; Eretz Israel was the term used by the Jewish community. The region's original name, Palestina Syria, was given to it by the Romans when they conquered what had formerly been the independent Jewish Kingdom.

- [iv] . Over time, Jewish dancers include Guglielmo Ebreo (the Jew; born before 1440 in Pesaro, Italy), Adolph Bolm, Marie Rambert, and Alicia Markova.

- [v]. When Israel was founded, the official view was that immigrants should discard their cultures of origin in order to create a new Israeli culture. Lately, this attitude has been changing, and now immigrants are encouraged to preserve their unique ethnic cultural heritage (Ronen 2000, 84-89).

- [vi]. Tel Aviv, to this day Israel's center of cultural activity, was founded in 1909 next to Arab Jaffa. In 1920 there were 2,084 people living in Tel Aviv.

- [vii]. These nationalistic aspirations were expressed in the founding of Habima Theater in Moscow in 1918, where plays were performed in Hebrew for the first time. The Habima Theater immigrated to Palestine in 1927.

- [viii]. Mizrahi (Oriental) Jews are Jews from Arab countries, including Yemenite and Sephardic Jews. The term Sephardi refers to Jews who lived in Spain and Portugal until they were expelled in 1492, many of whom settled in Middle Eastern countries as well as North Africa, the Levant and various European countries. The word Mizrahi literally means "eastern" and refers to Jews from North Africa and the Middle East, who do not necessarily trace their ancestry to the expulsion from Spain, and to their Arab culture.

- [ix]. The construction of the Eden, considered the first modern cinema in Eretz Israel, was completed in 1920. It had a wooden stage and a front curtain, on which commercials were projected. When dancers needed to cross from one side of the stage to the other, they had to walk around through the sandy street. It was situated within walking distance from Susan Dellal Center, where most of the dance activity in Israel takes place today.

- [x]. Golinkin had conducted the Russian opera singer Feodor Ivanovich Chaliapin. The Opera performed a selection of operas from around the world.

- [xi]. Mussia Daiches was later interned in Nazi concentration camps, and despite being totally crippled by Joseph Mengele's experiments on her legs she survived. After World War II she immigrated to the United States, where she lived with her husband and became a poet and painter.

- [xii]. The period of cultural isolation began in 1939 when World War II began, and continued through the Israeli War of Independence in 1948 to the 1950s. Between 1948 and 1951 approximately 700,000 people immigrated to Israel, some of them holocaust survivors and most from Jewish communities in Arab countries, including the Yemenite Jewish community. These years are called "the austerity period," owing to the economic difficulties that prevailed.

- [xiii]. Hassia Levy Agron was a pupil of Shoshana Ornstein and Else Dublon. She was the first Israeli dancer to study with Martha Graham in New York in the early 1950s (Perstein-Kaduri, 2002).

- [xiv]. A kibbutz is a cooperative agricultural settlement. The first one was created by the Sea of Galilee in 1909, and then many were established throughout Israel.

- [xv]. Companies touring in Israel during the early 1950s included Ballets des Champs-Élysées, Roland Petit's Ballets de Paris, London Festival Ballet, Pearl Primus (1951), and Talley Beatty (1952).

- [xvi]. In 1955 Martha Graham's company went on an official U.S. government-sponsored tour to the Far East, which ended in Iran. Following Batsheva de Rothschild's initiative, and with her funding, the company continued the tour and came to Israel in 1956.

- [xvii]. Katia Delakova and Fred Berk came to Israel on tour in 1949 and then returned to the United States. Two years later, Delakova returned alone to Israel, and stayed until 1957 (Ingber 1985, 58-61).

- [xviii]. Graham's dances in the Batsheva repertory in the 1960s include Herodiade, The Learning Process (Cited from the program: "In the process of learning, scenes of various works are revived in untheatrical surroundings. We are attending a rehearsal in which the dancers have their first opportunity to appear in characters from Martha Grahams`s Clytemnestra"), Errand Into the Maze, Saraband from Dark Meadow, Diversion of Angels, Embattled Garden, and Cave of the Heart. In 1974 Graham created Dream – Fantasy after Jacob`s dream) specially for Batsehva. Ohad Naharin danced the role of one of the two sons.

- [xix]. Hill-Sagan settled in Israel, and his original works entered the repertories of Bat-Dor, Batsheva, and the Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company. He returned to the United States briefly before his death and choreographed for Philandanco and Alvin Ailey. His ashes are buried in Kibbutz Ga`aton.

- [xx]. George Balanchine's dances in the repertory of the Israeli Ballet include Serenade, Concerto Barocco, Agon pas de deux, Four Temperaments,and Symphony in C.

- [xxi]. In 1492 all Jews were banished from Spain by King Ferdinand, and they scattered all around the Mediterranean and Western Europe.

- [xxii]. Carolyn Carlson came to Israel on tour with the Paris Opera Experimental Theater in 1977, Meredith Monk gave a workshop in Tel Aviv in 1982, and in that same year Kei Takei came to Israel with the Moving Earth Company and choreographed Light Part 11 for the Kibbutz Contemporary Dance Company.

- [xxiii]. Mirali Sharon studied with Nikolais and Cunningham in New York and then came back to Israel and worked with Batsheva and Bat-Dor in the 1970s. Sharon and Oshra Elkayam were among the few Israeli choreographers who created for the two companies in the 1970s.

- [xxiv]. Valery Panov was a soloist in the Kirov Ballet in St. Petersburg who was famous for his tenacious struggle to leave the Soviet Union. He immigrated to Israel in 1974, and later directed several European ballet companies.

- [xxv]. In the mid-1970s, many Jews immigrated to Israel from the Soviet Union, followed by approximately a million more who immigrated in the 1980s.

- [xxvi]. There are approximately 80,000 Ethiopian Jews in Israel today. Some arrived by way of a secret flight, dubbed the Moses Operation, through the Sudan desert in the early 1980s. Others came in 1991 through Addis Ababa in the Shlomo Operation, during which 15,000 Ethiopians were flown to Israel in twenty-four hours.